Stepping Through Memoization in Haskell

To better understand how memoization works with Haskell’s lazy evaluation, let’s walk through a simple example step by step. As a learning tool, we’ll examine a simple function that raises the number two to a the power of whatever number is given as input. Let’s begin by improving the naive implemenation of the function that we explored in the previous post.

Naive Implementation

Consider the naive implementation :

r_two_to_power :: Int -> Integer

r_two_to_power 0 = 1

r_two_to_power n = r_two_to_power(n-1) + r_two_to_power(n-1)This implementation returns the correct result, but it could be improved to become much faster with memoization.

Visualization

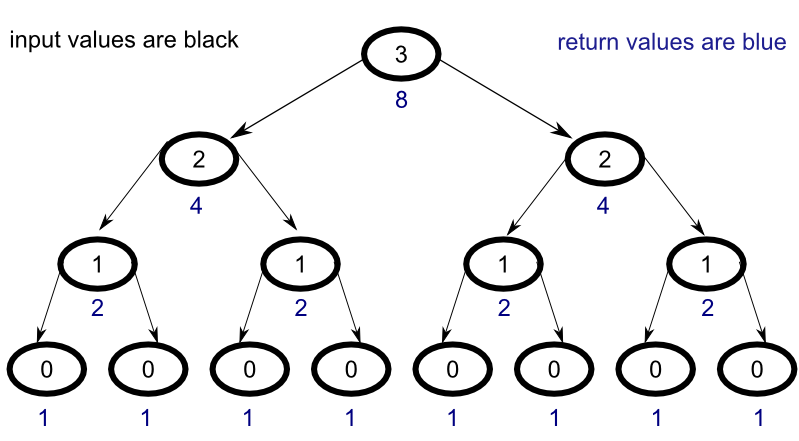

To understand why the naive implementation is so inefficient consider the following diagram :

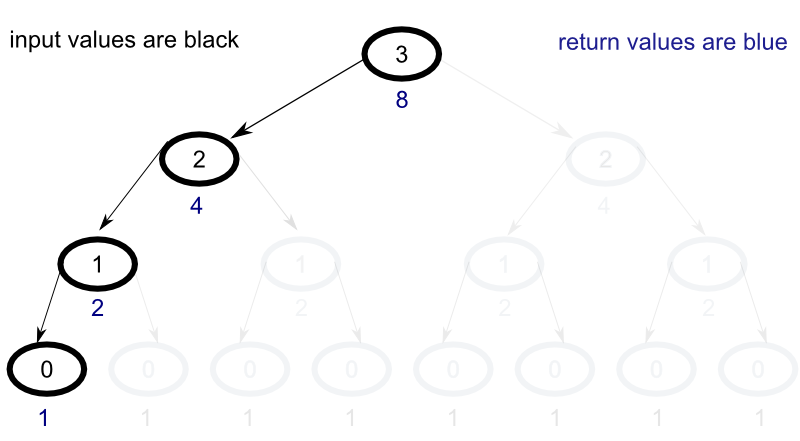

For every node in the tree, all child nodes must be evaluated in order to return their results to the parent node. Unfortunately, this ends up causing the same problem to be evaluated over and over again across multiple levels. For efficiency, what we would really like to produce is a process that looks more like the following :

In our new model, the number of calculations for each additional step expands linearly as opposed to exponentially, but, in order to accieve this end, we will need to create a memoized implementation of the function.

Memoized Implementation

The memoized implementation will look very similar to the naive implementation, but with a few key distinctions. We’ll walk throught the differences line by line.

m_two_to_power :: Int -> Integer

m_two_to_power = (map two_to_power [0 ..] !!)

where two_to_power 0 = 1

two_to_power n = m_two_to_power(n-1) + m_two_to_power(n-1)Explanation

Let’s start from the beginning.

m_two_to_power :: Int -> IntegerFor the first line, the only difference from the naive implementation is that we’ve switched the leading letter from ‘r’ to ‘m’ to indicate that this is a memoized version of the function. The second line is where things start to get interesting:

m_two_to_power = (map two_to_power [0 ..] !!)Here we define all cases of m_two_to_power as mapping to the corresponding output of the function two_to_power given the same input.

In haskell, “[0 ..]” means a list that begins at zero and continues on forever. This type of operation is only possible because of Haskell’s lazy evaluation. Because nothing from the list has been called, the list does not currently need to be evaluated so the operation is valid. The double exclamation points tell Haskell to index the list.

But wait! The function “two_to_power” has not been defined! Won’t this break the function? I’m glad you’ve asked. To understand what’s going on, let’s look at the next line.

where two_to_power 0 = 1In Haskell, you can define sub-patterns after the where clause which can be called within the main fuction body. Here a base case is defined for the sub-pattern “two_to_power”.

two_to_power n = m_two_to_power(n-1) + m_two_to_power(n-1)In the final line, the general case for “two_to_power” is defined recursively in terms of its parent function. In order to understand, how this works, let’s walk step by step through an example.

Example

Let’s step through the function when we input the value of 3.

m_two_to_power 3First the function, m_two_to_power, looks to the mapped sub-pattern, two_to_power, for a value. Since the input does not match the sub-pattern’s base case, the n case pattern is evaluated for the input 3.

two_to_power 3 = m_two_to_power(3-1) + m_two_to_power(3-1)Similarly, when the right leg of the sub-pattern is evaluated for the values of 2 and 1, we see the same recursive pattern, but, once we the input 0, something interesting happens:

the base case is satisfied and now the first value in the two_to_power[0..] list has been evaluated.

For a step by step walkthough, review the step table below :

Step Table

| Step | Input | Level-Node | Map | Recurses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 3-0 | [] | True |

| 2 | 2 | 2-0 | [] | True |

| 3 | 1 | 1-0 | [] | True |

| 4 | 0 | 0-0 | [0:1] | False |

| 5 | 0 | 0-1 | [0:1] | False |

| 6 | 1 | 1-1 | [0:1,1:2] | False |

| 7 | 2 | 2-1 | [0:1,1:2,2:4] | False |

| 8 | 3 | 3-0 | [0:1,1:2,2:4,3:8] | False |